The Win That Changes Nothing

A provider spends 30 minutes on a peer-to-peer call. She walks through the clinical evidence, explains why the specific set of criteria doesn't fit this patient, and gets the override approved.

Then she says: "You know, this criterion should really be updated. The guidelines changed earlier this year."

The clinical pharmacist on the other end nods. "I hear you. I'll pass that along."

The call ends. Nothing is logged. The next patient with the same profile will face the same fight.

The denial was overturned. The policy remains untouched.

The Problem Isn't Appeals. It's Standing.

Health plans have a well-defined process for appealing individual coverage decisions. If a claim is denied, there's a pathway: internal review, second-level appeal, and uncommonly, cases sent off for independent, external review.

That system works—for individual cases.

But what happens when the issue isn't the denial, but the coverage criteria itself?

What if the policy is clinically outdated, overly restrictive, or misaligned with current evidence? What if the same denial happens again and again—not because the cases are weak, but because the rule is?

There is no formal process to challenge the policy itself.

The Individual Path (Exists)

For a single patient, the system is structured and familiar:

Step | Who Decides | Outcome |

Initial determination | Plan or PBM clinical team (often automated) | Approved or denied |

First-level appeal | Internal review (PBM or plan) | Upheld or overturned |

Second-level appeal | Different internal reviewer (plan or TPA) | Upheld or overturned |

External review (IRO) | Independent organization | Final determination |

This pathway can resolve a case.

What it cannot do is change the criteria. The next patient with the same profile encounters the same barrier. The provider makes the same phone call. The same arguments. The same 30 minutes.

The system processes cases. It’s not guaranteed to learn from them.

The Policy Path (Doesn't Exist)

If someone believes the coverage criteria itself is flawed, who has formal standing to raise that concern?

Stakeholder | Current Channel | Formal Standing? |

Patient | Notes included in appeal | No |

Provider | Peer-to-peer calls, letters | No |

Manufacturer | Requests to P&T | Informal access, discounted credibility |

Employer group/ Plan sponsor | Contract negotiations | Indirect |

Advocacy organizations | Public or regulatory complaints | No direct standing |

Everyone can knock om the door, but no one has a key.

How Policy Concerns Actually Surface Today

In practice, policy challenges emerge in fragmented, informal ways:

Manufacturer requests Pharma reps present new data to P&T and request criteria updates. They have the most access—but the commercial incentive limits credibility. The ask may get discounted before it's heard.

Appeal narratives Providers cite guidelines or evidence in appeal packets: "This criterion is inconsistent with the 2023 ADA Standards of Care." These comments may be read. They're probably not documented formally. On occasion, they’ll trigger review.

Peer-to-peer conversations A denial is overturned after clinical discussion. At the end of the call, someone mentions the policy should be updated. The conversation ends and the clinician on the other end gets back to their endless work queue.

Employer frustration at renewal "Why are we denying a drug our employees clearly need?" But renewal negotiations focus on pricing and administration, not always on clinical criteria. The concern is noted, not actioned, and likely weighed against strategy initiative.

Regulatory complaints Occasionally effective. Often slow. Rarely specific enough to drive targeted policy change.

The signal exists. The system doesn't collect it.

Why This Matters

When the only way to address a problematic policy is through repeated individual appeals, the burden falls entirely on patients and providers.

Each appeal is a solo act. The physician arguing for her patient. The pharmacist navigating the override. The patient waiting, worrying, wondering if the medication will come through.

They win or lose. Either way, the policy stays the same.

Coverage policy becomes reactive instead of adaptive—not because decision-makers don't care, but because there's no mechanism to aggregate, evaluate, and escalate policy-level concerns.

This is a governance gap.

And it has a predictable consequence: policies calcify during some stretches. The most targeted effort drafting criteria was 2 years ago, based on evidence from four years ago, continues to govern access today—not because it's still correct, but because of bandwidth, efficiency or lack of pushback.

What Would a Formal Channel Look Like?

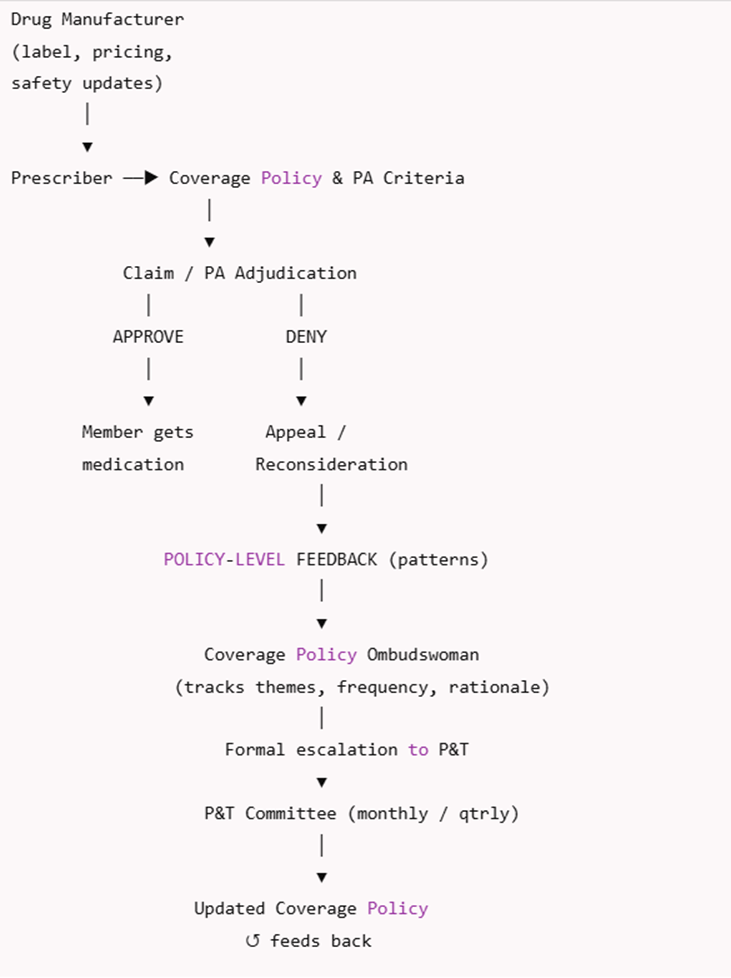

Imagine a role that sits outside individual adjudication: a Coverage Policy Ombudswoman.

Not someone who overturns denials. Someone who ensures patterns are visible.

Her job:

Receive policy-level feedback—not case appeals, but concerns about criteria themselves

Track recurring themes across appeals, denials, peer-to-peer notes, and provider input

Document frequency, rationale, and clinical context

Escalate formally to P&T with structured summaries

Close the loop by ensuring outcomes feed back into policy updates

She doesn't weaken P&T authority. She strengthens it—by ensuring the committee sees what's happening downstream.

What This Changes

With a formal feedback channel:

Recurrent issues are no longer anecdotal

P&T discussions are informed by real-world friction

Policy updates become proactive instead of reactive

Transparency improves without politicizing decisions

Most importantly: disagreement with coverage criteria no longer depends on who complains loudest or who has the best access.

Standing is institutionalized.

Why This Is Rare (But Not Unprecedented)

Public programs already recognize this need in limited ways. Medicare has National Coverage Determinations with public comment periods. Medicaid has formal reconsideration pathways. State insurance departments field complaints that occasionally trigger review.

Employer-sponsored commercial coverage largely has none of this.

That doesn't mean the gap is inevitable. It means it hasn't been designed for.

The Watchdog Frame

I'm not proposing legislation. I'm not drafting model policy.

I'm naming a structural gap that most people inside the system feel but rarely articulate:

You can appeal your denial. You cannot appeal the policy.

When feedback is informal, it evaporates. When policies can't be formally challenged, they calcify. When the same concern arises fifty times but has nowhere to go, the system isn't learning—it's just processing.

The appeals process asks: Was this case decided correctly?

Governance asks: Is the rule itself correct?

One of those questions has a process. The other doesn't.